An old man who learns of his stomach cancer attempts to make the most out of his numbered days in Kurosawa’s powerful examination of body and soul, living and dying, and the societal conditioning of the common man in misjudging others.

Review #3,056

Dir. Akira Kurosawa

1952 | Japan | Drama | 143min | 1.37:1 | Japanese

PG (passed clean)

Cast: Takashi Shimura, Nobuo Kaneko, Shin’ichi Himori

Plot: After learning that his stomach cancer has left him with less than a year to live, a Tokyo bureaucrat struggles to reconcile with his impending death and begins looking for ways to make his remaining days meaningful.

Awards: Won Special Prize of the Senate of Berlin & Nom. for Golden Bear (Berlinale); Nom. for Best Foreign Actor (BAFTA)

Source/Distributor: Toho

Accessibility Index

Subject Matter: Moderate – Mortality; Terminal Illness; Finding Meaning; Bureaucracy; Misjudging People

Narrative Style: Slightly Complex

Pace: Slightly Slow

Audience Type: Slightly Arthouse

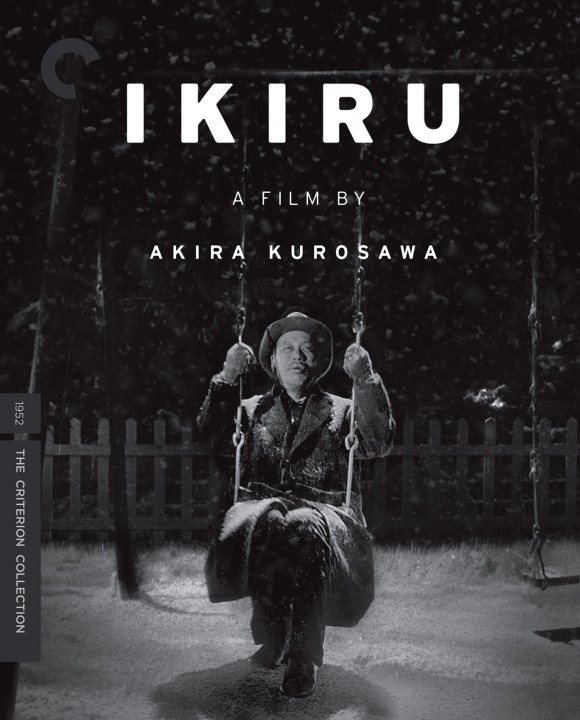

Viewed: Criterion Blu-ray

Spoilers: No

I first saw Kurosawa’s Ikiru more than 15 years ago on a terrible transfer with even more appalling subtitles. It was one of those $5-a-piece DVDs with a fake Criterion cover that was conspicuously paraded outside a major hypermart, and I remembered watching it left me uninterested.

Folks, don’t settle for less—always try to find the best possible copy for these kinds of universally regarded great films. Revisiting it again after a long time, on a proper Criterion Blu-ray with a new 4K transfer, it feels like a resurrection, which is just as well, as Ikiru is about the resurrection of an old man, not at all holy but simply ordinary.

Played by Takashi Shimura in arguably his finest ever performance, Watanabe learns that he has stomach cancer and has only months left to live. Kurosawa opens the film with an X-ray of his tummy, signalling that this will not be a typical narrative but an examination of a man’s body—his tired, ailing shell, but also soul, miserably trapped in stifling government bureaucracy and infinite paperwork for much of his adult life.

“I can’t afford to hate people. I don’t have that kind of time.”

This is a man who has not lived, but hopes to make amends in his withering days by attempting to push through the construction of a public park with a playground for kids. Though structurally less radical than his earlier Rashomon (1950), Ikiru is still unconventionally split into two parts—life and death; or is it the opposite, a resurrection?

Kurosawa goes further by using the ambiguous duality to attack the societal conditioning of the common man. Watanabe ceases to be understood in life by others (his son, colleagues, etc.), yet in death, he becomes a subject of misunderstanding by the very same people, his intentions misread, his life misjudged.

In view of this, Ikiru, like Rashomon, may seem endlessly bleak, as if we are condemned to an eternity of “mis-ses”. But like a lighthouse in an ocean of black, Watanabe stands as a solitary figure of perseverance and compassion, values that many of us need reminding of from time to time.

Such is his renewed sense of community spirit (it is no more body and soul, but simply the lingering essence that fleetingly lives and dies in others) that Kurosawa would translate it back across space and time in his next film, the epic masterwork Seven Samurai (1954), a tale of courage, sacrifice and the heart to serve, which has since become mythic.

Grade: A

Trailer:

Music:

[…] Ikiru (1952) […]

LikeLike

Absolutely agree. A film that resonates to this day.

LikeLike

Indeed!

LikeLike