A quietly defiant and unconventional anti-war film, Melville turns passivity into resistance, using repetition, silence, and minute gestures to probe the human soul, as a highly-cultured Nazi officer installs himself in the home of an old Frenchman and his niece.

Review #3,064

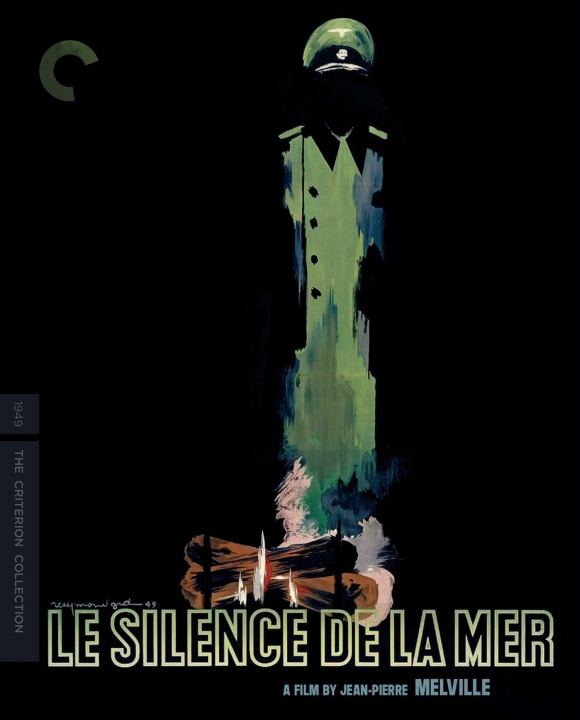

Dir. Jean-Pierre Melville

1949 | France | Drama, War | 87min | 1.33:1 | French & German

Not rated – likely to be PG

Cast: Howard Vernon, Nicole Stephane, Jean-Marie Robain

Plot: In a small town in WWII France, a German officer is billeted in the house of an elderly man and his niece, who resist the occupation by refusing to interact with him, even as he speaks to them candidly about his life and hopes for the future of France and Germany.

Awards: –

Source/Distributor: Gaumont

Accessibility Index

Subject Matter: Moderate – Nazi-Occupied France; Silent Resistance; Hopes & Dreams

Narrative Style: Straightforward

Pace: Slightly Slow

Audience Type: Slightly Arthouse

Viewed: Criterion Blu-ray

Spoilers: No

Being part of the French Resistance during WWII, it is not surprising to see Jean-Pierre Melville adapt for his first feature film a novella clandestinely published in Nazi-occupied France. A piece of text that channelled the spirit of defiance against the oppressors, Le silence de la mer (or The Silence of the Sea) was unique in its approach—instead of loud, galvanising roars for salvation, we get extreme passivity and inaction.

A Nazi officer installs himself in the house of an old Frenchman and his niece, where he stays for some time. Disgusted by his presence, they remain completely silent, treating him like a ‘ghost’—their refusal to engage in any conversation with him becomes their only weapon.

Yet, this is no ordinary Nazi, but one who is cultured and loves French culture, art, literature, and music. He imagines a future where there is a symbiotic ‘marriage’ between their two countries. All this waxing lyrical about France, however, falls persistently on deaf ears.

Melville’s attempt to make the source material more cinematic is admirable, as little gestures like glances and movements of hands become amplified in close-ups.

The repetitive nature of the scenes (the Nazi officer joins them every evening, sharing his thoughts) may at first feel uninteresting, but once we get used to the ‘modus operandi’, or less charitably, the source’s limitations in setting and approach, we begin to understand why this incessant repetition (one that would drive anyone mad) becomes the key to unlocking the human soul, yes, even the soul of a Nazi.

“And so, he had left. And so, he submitted, like the others, like all the others of that miserable nation.”

Here is a man who has ambitious dreams of camaraderie and fellowship, free from blind patriotism, but becomes bogged down by the violent machinery of an extremist ideology, one that he finds impossibly difficult not to submit to.

As such, one might see Melville’s work as an unconventional anti-war film, and for both sides—the French duo resist by not speaking (how tough it is that they must disengage even with a potential ally that they could very well ‘convert’), while the sole German speaks his mind in resonating ways (how tough that he stands alone with his views that would undoubtedly court treasonous trouble with his superiors, even in the ‘safe space’ that is his enemy’s house).

To speak or not to speak? These are the quiet moral dilemmas that must be overcome, even transcended. Those who are more familiar with Melville’s later works, particularly his crime pictures like Le samourai (1967) and Le cercle rouge (1970), will find this to be aesthetically and tonally many miles apart, much like an antecedent to Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951).

I feel like I’ll appreciate Melville’s highly influential work even more in a second viewing, in the context of post-war French cinema.

Grade: B+

Promo Clip: