An exquisite and meditative biopic about a Japanese tea master who became influential with the shoguns during the 16th century as Teshigahara conflates the personal with the political in a beguiling way.

Review #2,973

Dir. Hiroshi Teshigahara

1989 | Japan | Drama, Biography, History | 135min | 1.85:1 | Japanese & Portuguese

PG (passed clean)

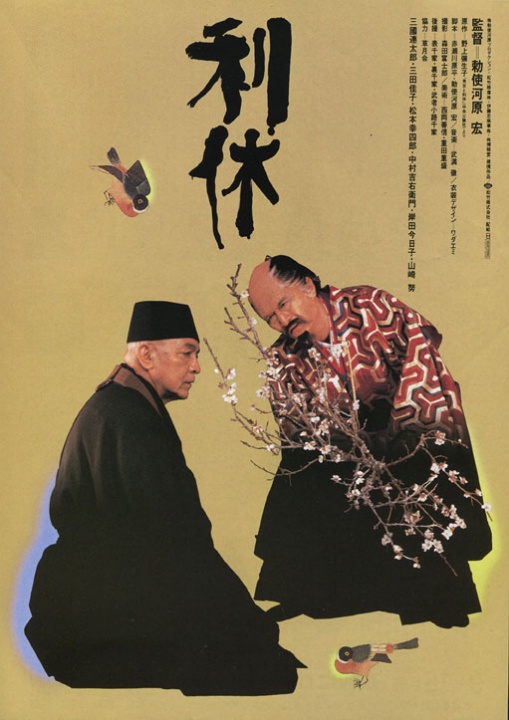

Cast: Rentaro Mikuni, Yoshiko Mita, Tsutomu Yamazaki

Plot: Late in the 1500s, an ageing tea master teaches the way of tea to a headstrong Shogun.

Awards: Won C.I.C.A.E Award – Panorama (Berlinale)

Distributor: Shochiku

Accessibility Index

Subject Matter: Moderate – Tea Master & Tea-Making; Shogunate Politics

Narrative Style: Slightly Complex

Pace: Slightly Slow

Audience Type: General Arthouse

Viewed: Screener

Spoilers: No

Best known for Woman in the Dunes (1964), Hiroshi Teshigahara wasn’t someone who would immediately come to mind for any cinephile rattling off the names of great Japanese directors.

Although he hadn’t made as many features as his New Wave compatriots like Nagisa Oshima or Shohei Imamura, Teshigahara was as enigmatic a filmmaker as any from that vital generation.

His late career effort and penultimate feature, Rikyu, is a brilliant piece of work. The director’s lifelong fascination with tradition, art and craft reached some kind of reflective and meditative zenith with this exquisite biopic on the titular master, whose tea-making not only enthralled his guests (many of whom were high-profile shoguns), but also elevated his influence in the politics of the time.

In this case, it’s the 16th century, as the all-powerful if spitefully controlling Lord Hideyoshi strikes up a close friendship with Rikyu, as he learns the way of the tea from the wise man.

Some had found Tsutomu Yamazaki’s performance as Hideyoshi distractingly ‘cartoony’, but I loved how his childish tantrums contrasted greatly with Rikyu’s zen-like demeanour.

“You always insist that the tea ceremony epitomises simplicity and naturalness.”

Hideyoshi has grand plans of invading China though his advisors and other Lords are ambivalent about it. Teshigahara guides us through the political intrigue with an assured hand, accompanied occasionally by the ominous strains of Toru Takemitsu’s music.

There is a sense of inevitability as Rikyu finds himself being exploited; at the same time, he also overreaches in some aspects beyond his skillset, ‘spilling the tea’, so to speak.

Rikyu sometimes feels like an Ozu film, only much more stately and far less contemporary. Teshigahara takes his time and lets his film ferment and brew, emphasising stillness and precise gestures. As such, it gains its power gradually and cumulatively, but most importantly, organically.

At once familiar and seemingly conservative in its storytelling (even though it was made in the late ‘80s, the film recalls the jidai-geki i.e. period dramas of the ‘50s like Gate of Hell), yet feels quietly radical in its treatment of themes of dominance and subservience, Rikyu conflates the personal with the political in a beguiling way, creating a storm in a teacup, as they say, but with profound implications.

Grade: A

Trailer:

Music: