Sublime, meditative yet elusive, Hamaguchi’s ecological drama isn’t that simple a concoction about capitalist expansion and its impact on the marginalised, exploring its theme on a more primal, anterior level.

Review #2,804

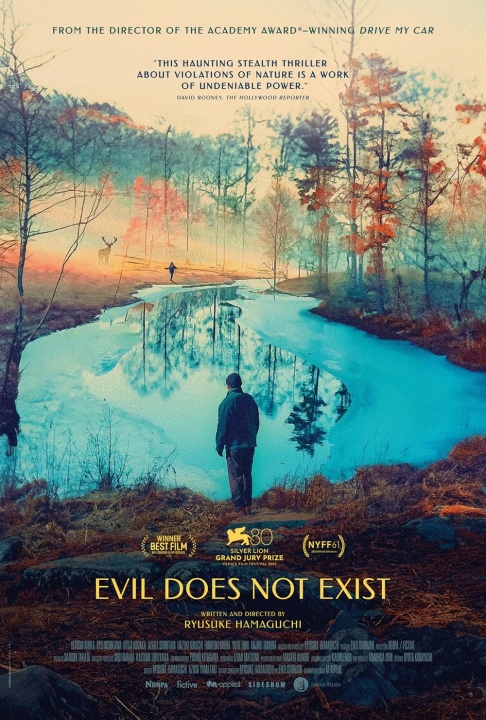

Dir. Ryusuke Hamaguchi

2023 | Japan | Drama | 107 min | 1.66:1 | Japanese

PG (passed clean)

Cast: Hitoshi Omika, Ryo Nishikawa, Ryuji Kosaka, Ayaka Shibutani, Hazuki Kikuchi

Plot: Hakumi and his daughter Hana, living in Mizubiki Village near Tokyo, face a threat when a planned glamping site near their home risks the local water supply. As company reps from Tokyo reveal the negative impacts, village unrest and ecological dangers jeopardize their traditional way of life.

Awards: Won Silver Lion – Grand Jury Prize & FIPRESCI Prize (Venice)

International Sales: m-appeal (SG: Anticipate Pictures)

Accessibility Index

Subject Matter: Moderate – Ecosystem & Balance; Father-Daughter Relationship; Capitalism

Narrative Style: Slightly Complex

Pace: Slightly Slow

Audience Type: Slightly Arthouse

Viewed: Oldham Theatre (as part of Asian Film Archive’s Releases programme)

Spoilers: No

Evil does exist, whether innate, under pretence or perceived, and this is where Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s latest work ‘triumphs’, though I have reservations about using that word too generously.

While the soul of the film can be sublimely felt, Evil Does Not Exist somehow pulls the rug from right beneath us, which will divide audiences.

Some may find the film suddenly elusive and emotionally confusing; others may feel that it unexpectedly elevates the work to an almost metaphysical, mythical level. You likely won’t see, for instance, Hirokazu Kore-eda, pulling off something like this.

But whatever it is, Hamaguchi remains a fascinating filmmaker as he doesn’t stick to conventions even as he sometimes draws wilfully from them.

The film’s meditative quality (backed by an ambient score from Eiko Ishibashi, who also scored Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car) also allows viewers to immerse in its deliberate pacing and exceptional cinematography.

“They showed up out of nowhere yesterday.”

In hopes of getting subsidies and funding, a company seeks to develop and promote a ‘glamping’ (glamour camping) site that sits right in the middle of a village and its peaceful inhabitants.

Worried that a poorly strategised septic tank will pollute the spring water that they depend on, the villagers attempt to persuade the company representatives to better strike some kind of eco-balance, or else they will not support their project.

Through this ecological drama, Hamaguchi obviously paints the ‘evil’ that is the encroachment of capitalism into an isolated local community.

This is not new, and certainly so for Japanese cinema, as we can trace it back thematically to films such as, for example, Shohei Imamura’s Profound Desires of the Gods (1968).

However, Evil Does Not Exist isn’t that simple a concoction about capitalist expansion and its impact on the marginalised—it works on a more primal, anterior level, telling of a time before all of that, of ‘intervention’ before ‘disruption’.

Grade: B+

Trailer:

Music: