Parajanov’s free-wheeling breakthrough film is a remarkable sensorial work that could hardly contain its dizzying energy—a showcase of a filmmaker at the height of his artistic expression.

Review #1,503

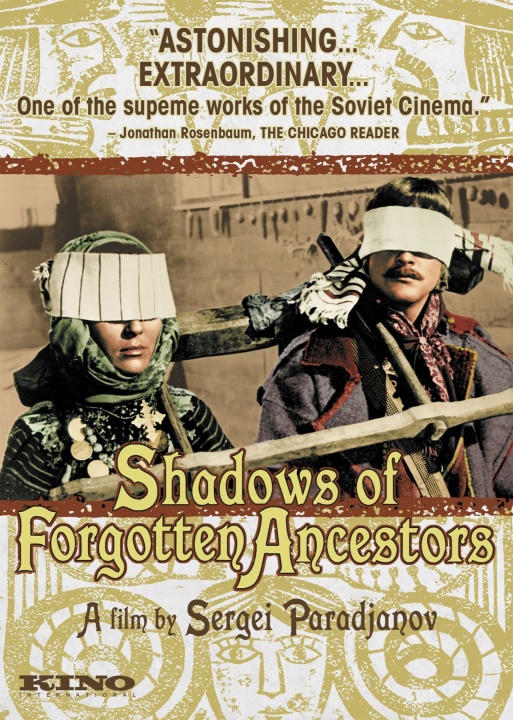

Dir. Sergei Parajanov

1965 | Soviet Union | Drama / Romance| 97 mins | 1.37:1 | Ukrainian

M18 (passed clean) for some nudity

Cast: Ivan Mykolaichuk, Larisa Kadochnikova, Tatyana Bestayeva

Plot: Ivan is drawn to Marichka, the beautiful young daughter of the man who killed his father. But fate tragically decrees that the two lovers will remain apart.

Awards: –

Source: Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre

Accessibility Index

Subject Matter: Moderate

Narrative Style: Slightly Complex

Pace: Slightly Slow

Audience Type: General Arthouse

Viewed: National Museum of Singapore – Perspectives Film Festival

First Published: 24 Oct 2017

Spoilers: No

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is a rare film that you should see, by the legendary Soviet filmmaker Sergei Parajanov.

It is not just his breakthrough film, one that would pave the way for him to make such landmark works as The Colour of Pomegranates (1969), and later on in his career, The Legend of Suram Fortress (1985) and Ashik Kerib (1988), but it is also a brilliant artistic achievement that showcases a filmmaker at the height of his powers.

It is at once unlike any other film that you have seen—though that could be said of most of his works—and a strong example of the malleability of cinema, in ways that show the medium to be boundless in its form, structure and style.

Set in a Carpathian village in the mountainous region of Western Ukraine, Shadows centers on Ivan, who falls in love with Marichka, the daughter of his father’s killer. We follow Ivan in his fatalistic journey as he travels to find work—and in the process be entranced by Parajanov’s highly-sensorial film.

With dazzling camerawork that could hardly contain the film’s dizzying energy, one might find the film bursting with colourful life—in all of its joy and misery. Even the use of sound is remarkable, particularly its flavourful ethnic music.

In a few scenes, large, long horns called trembitas are blown, producing a sound that reverberates through space and time, a sonic marker of the unique Hutsul culture, similar to what the Tibetan horn and the didgeridoo do for Tibetan/Mongolian Buddhists and indigenous Australians respectively.

The sound of the trembita also amplifies Parajanov’s ethnographic intention to bring to screen a beloved Ukrainian book of the same name by Mykhailo Kotsuibinsky.

There’s a wild paganistic spirit to the filmmaker’s approach, which in the context of the Soviet’s brand of dreary Socialist Realism at that time, seems so out-of-this-world and blatantly rebellious.

It is no wonder that Parajanov’s cinema was deemed too anarchic for the Soviet authorities, foreshadowing his persistent persecution for much of his later life.

The sheer invention and imagination of Shadows continue to inspire filmmakers—its greatest legacy is to show that cinema as a storytelling and stylistic medium has no rules.

Grade: A

Trailer:

[…] Parajanov, Sergei […]

LikeLike

[…] Parajanov, Sergei […]

LikeLike