My personal favourite of all of Hitchcock’s works, this intelligent and suspenseful treatment on scopophilia and scopophobia in relation to gender, gaze theory and paranoia is also one of his finest achievements.

REVIEW #849

Dir. Alfred Hitchcock

1954 | USA | Drama/Mystery | 112 mins | 1.37:1 | English

PG (passed clean)

Cast: James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Raymond Burr

Plot: A wheelchair bound photographer spies on his neighbours from his apartment window and becomes convinced one of them has committed murder.

Awards: Nom. for Golden Lion (Venice); Nom. for 4 Oscars – Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Cinematography, Best Sound

Distributor: Universal

Accessibility Index

Subject Matter: Moderate – Paranoia, Privacy

Narrative Style: Slightly Complex

Pace: Normal

Audience Type: Slightly Mainstream

Viewed: DVD

First Published: 25 Jan 2013

Spoilers: Mild

Even though I consider Vertigo (1958) to be the greatest Alfred Hitchcock picture of all time, Rear Window remains to be my personal favorite. In the complete oeuvre of Hitchcock, Rear Window firmly occupies the very top shelf, together with such classics as the aforementioned Vertigo, North by Northwest (1959) and Psycho (1960).

It is a great film, not only from a critical standpoint but also from the audience’s point-of-view. For a 1950s picture, it has not dated one bit and offers an excellent introspective night’s entertainment for the whole family.

A groundbreaking film study on the theme of voyeurism, Rear Window has no equal. Even its contemporary remake, Disturbia (2007), isn’t even a third as good and is an insult to what Hitchcock originally planned to achieve with this picture.

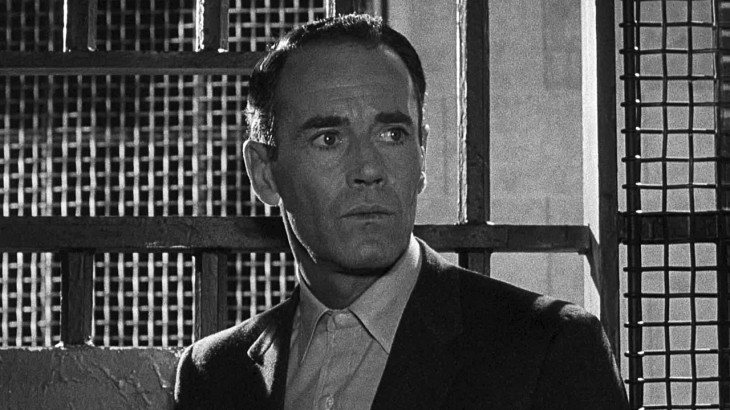

Starring the legendary James Stewart as Jeff, a wheelchair-bound photojournalist who met with an accident but is only a week from full recovery, and the elegant Grace Kelly as Lisa, Jeff’s fiancée who slowly becomes involved in one of the most intriguing plots ever written, Rear Window is a brilliant concoction of drama, suspense, and dark humour.

This being a Hitchcock picture, there would certainly be a crime involved, or so we thought. Jeff thinks that one of his neighbours might have murdered and cut up his invalid wife. His detective friend, Doyle (Wendell Corey), however thinks that Jeff is delusional.

“Intelligence. Nothing has caused the human race so much trouble as intelligence.”

At this juncture, we are in doubt, yet this draws us further into the film. Later, Lisa and Stella (Thelma Ritter), Jeff’s personal nurse, become convinced of the possibility of such a heinous crime happening when their observations point to the suspect as a murderer.

Written by John Michael Hayes (To Catch a Thief, 1955; The Man Who Knew Too Much, 1956), the screenplay takes its time to develop the protagonist who spends nearly the entire film immobile in a wheelchair. Jeff’s immobility would become a plot device in the climax, which even by Hitchcock standards, is extremely tense.

A particular phone call seemingly sucks the air out of the picture, conveying a deep sense of dread and inevitability that is to come. Moreover, the use of ambient sounds as part of the film’s mise-en-scene, as well as to dictate the level of suspense is masterfully done.

Supporting characters are seen through the voyeuristic eyes of Jeff, and they are developed objectively through the lens of the camera. We sympathize with Ms. Lonelyhearts who longs for a man to love her, smile at Ms. Torso who flaunts her athletic body with graceful stretching motions, and observe with some degree of comic distance the rest of the folks in their apartments doing their private business.

The capturing of the ignorance of these characters towards a possible murder committed in front of their eyes marks one of the screenplay’s high points. In one scene, a dead dog is found. Its owners are devastated but for the rest, life goes on without sympathy. Are we not the same?

“Why would a man leave his apartment three times on a rainy night with a suitcase and come back three times?”

For its time, Rear Window is remarkably advanced from a technical standpoint. The cinematography by Robert Burks brilliantly captures exterior and interior shots in single takes without problems arising from differences due to the exposure of light. The transition is so smooth that it is impossible to tell when natural or artificial light is used in these shots.

Burks’ camerawork makes us willing participants in the spying game, drawing us into the sinister world of Hitchcockian terror. Like David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), Rear Window explores the concealment of Man’s hideous nature under the façade of seeming normalcy. It takes a keen eye to see what’s wrong underneath all the pleasantries.

Rear Window is not only a masterpiece of film direction and screenwriting, but also an influential force that continues to inspire contemporary filmmakers to deal with the issues of privacy, intrusion, and paranoia in the modern world.

One of the best examples would be Michael Haneke’s Cache (2005), with its dramatic treatment of the ethics of video surveillance a cinematic offshoot of Hitchcock’s work.

Rear Window is one of the greatest films of all time, and with each repeated viewing, its thematic elements not only become more salient in the world we live in, but also increasingly unsettling.

Grade: A+

Trailer:

Music:

[…] Hitchcock, Alfred […]

LikeLike

[…] Hitchcock, Alfred […]

LikeLike

[…] Hitchcock, Alfred […]

LikeLike

[…] Hitchcock, Alfred […]

LikeLike

[…] as far as Ozon is concerned, the essence of In the House is best manifested in the Rear Window-esque epilogue that brilliantly captures the myriad of desires we would have liked to vicariously […]

LikeLike

[…] references to Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993), Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), and not to forget Kershner’s The Empire Strikes Back (1980) are also nicely weaved into […]

LikeLike

[…] a voyeuristic setup that immediately calls to mind Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), Kieslowski’s film explores love, passion and sex with a potent sense of emotion and human […]

LikeLike

[…] Hitchcock, Alfred […]

LikeLike

[…] Hitchcock, Alfred […]

LikeLike

[…] Hitchcock, Alfred […]

LikeLike

[…] Hitchcock, Alfred […]

LikeLike

[…] Hitchcock, Alfred […]

LikeLike

[…] Hitchcock’s follow-up to one of his greatest films, Rear Window (1954), was a middling effort in comparison, though Cary Grant and Grace Kelly combined their star […]

LikeLike